Censorship across the World – „Die Kasseler Liste“

The Unlikely Absence of Censorship

“What once has been printed belongs to the world for all time. Nobody has the right to destroy it. Whoever does this offends the world much more severely than the author of the book that has been destroyed, no matter of which kind it was.”

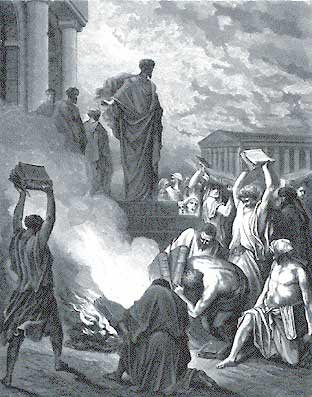

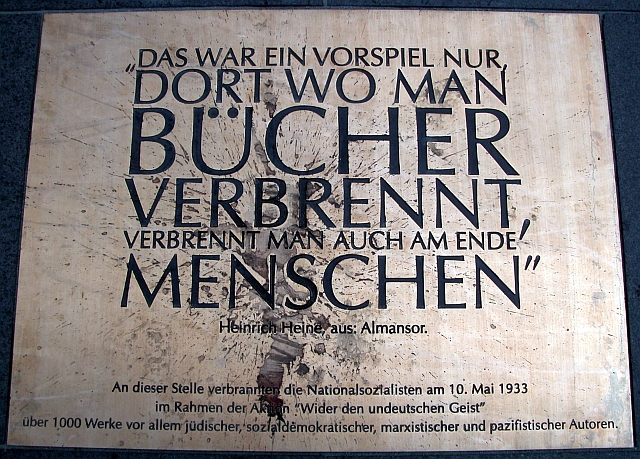

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s famous dictum from 1773 is a passionate outcry against censorship and an indictment of any limits imposed on the freedoms of expression and opinion. Illegitimate and inhuman: This is how he perceives the prohibition and, even more so, the burning of books, both of which were everyday occurrences in the era of Lessing, the Age of Enlightenment. But these practices persisted well into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. One might even go as far as to say that there has never been censorship that was so pervasive, that infiltrated all parts of private and public life as in the modern totalitarian states. In the germanophone world, we of course first and foremost think of the Third Reich and the German Democratic Republic.

Censorship is as just as old, but also just as young as literature itself. Books do not exist apart from state and social control mechanisms, both in restrictive systems and in open societies. To be sure, liberal democracies by and large have implemented constitutional controls that prevent any state-sponsored censorship. But even here, social, political and religious groups and institutions still exert various forms of censorship.

What is Censorship?

The debate on what should be considered censorship remains open, both in public and academic discourse. Legal definitions differ from definitions in the fields of Sociology, Philosophy, Literary Studies and Art History. All depends on which actors, practices and forms serve as criteria, on whether preventive or retroactive measures are being considered, etc. Common parlance often assumes that any means of controlling public opinion are tantamount to censorship. The result is not just an imprecise definition, but an inflationary use of the term that expands the scope of the term to the point that it becomes meaningless. As such, crying ‘censorship’ has become a preferred tool in the battle against those with whom we disagree. It is just as important, however, to rely not on a singular, fixed, constitutional understanding of the term. Chances are that such an understanding could not encompass the modern structural and systematic limits to the freedom of expression brought by the advent of the digital age. It is necessary to constantly engage with the term and the phenomenon, even in democratic societies that have supposedly overcome this problem.

When it comes to Die Kasseler Liste, we are working with a rather narrow and precise notion of censorship. We are dealing with banned books, i.e. text that existed as a manuscript or a published work and the circulation of which was prevented in part or in full, either preventatively or retroactively. We do not list as cases of interdictions that were based on criminal cases brought before a court in constitutional democracies. Rather, the list presents instances of censorship where institutional, systematic-structural control mechanisms limit the freedom of expression with a political, religious or moral motivation.

How Powerful is Literature?

A democracy without books is not a democracy.” Marta Minujín, the creator of the “Parthenon of Books” (documenta 14, Kassel 2017), celebrates the enlightened significance of the printed word. And she is right to do so. Even in the digital age the physical book remains an important factor for the ability of a society to critically reflect upon itself and others. At the same time, one may cynically evaluate the significance of literature by the efforts directed against it: People and institutions fear its power, its unpredictability. Censorship is thus informed by a particular understanding of the arts: Literature, according to this vision, has the power to significantly impact society, therefore it is necessary to silence this power. It is a vision that says less about literature and more about its perception. It makes apparent the uneasiness of the powerful, of the sovereign’s lack of sovereignty.

Nevertheless, the vision of a powerful and dangerous literature has little in common with reality, as recent research on censorship has shown. Reading a book does not automatically change a person and even less an entire society. Such notions ignore the independence of the readers (for instance their fidelity to identity-establishing world views) as well as the general complexity of social processes.

Indeed, a book almost never changes a human being. Repressive censorship, however, does: It makes people fearful, wary and tight-lipped. But censorship is not only unnecessary and harmful, most often it is also counterproductive. “What Rome prohibits, the people will most certainly read” – already in the early modern period this was general knowledge vis-á-vis the effects of the “Index Librorum Prohibitorum” issued by the Catholic Church. To this day, a book cannot hope for better advertisement or for a better endorsement than to be banned.

Censorship does not, however, always fail, at time it is indeed successful. To be sure, Werner Fuld, a leading scholar on censorship, remains optimistic, and he is not the only one to believe that the efforts of the censors will ultimately prove futile. In the end, ideas are always stronger than laws. In a similar vein, Marta Minujín’s “Parthenon of Books” was described in the press as a monument to freedom of thought, demonstrating that the collective memory of humankind is stronger than any form of censorship.

Such a broad perspective, however, obscures the very real and very grave partial victories of censorship. Censorship curtails the freedom of its victims, it complicates their lives and prematurely ends them in the most severe cases. It possibly eradicates ideas that could have shaped the future. Cross-checks are impossible: Nobody knows the history of concealed ideas.

No Save Havens

No matter how frequently the failures, the inefficacy and the self-defeating qualities of censorship become apparent, its proponents and agents continue to put their faith in their own control mania. The history of institutional censorship, from the early modern period to the present day, is by and large a history of its growth, its professionalization and systematization, of its pervasion of and proliferation throughout society, culminating in the surveillance apparatuses of modern totalitarian states. The end of censorship does not seem to be near.

Regardless of the demonstrable developments towards democratization across the world, people across the world continue to be persecuted due to their opinions and attitudes, the freedom of the press remains under attack, road blocks are set up along the access routes to knowledge. Even the archaic ritual of book burning persists to the present day, in the Middle East as well as in the USA, in England and Italy.

There are no safe havens, not even in democratic societies. In each society, freedom of expression must constantly be protected, inculcated and exercised. Do we, in fact, have more or less censorship today, more or less freedom than in the past? This question is difficult to answer, but an all-clear signal is not on the horizon.